THE TWO LETTERS WRITTEN BY PLINY THE YOUNGER ABOUT THE ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS IN 79 A.D.

LXV - TO TACITUS

Your request that I would send you an account of my uncle's

death, in order to transmit a more exact relation of it to posterity,

deserves my acknowledgments; for, if this accident shall be

celebrated by your pen, the glory of it, I am well assured, will be

rendered forever illustrious. And notwithstanding he perished by a

misfortune, which, as it involved at the same time a most beautiful

country in ruins, and destroyed so many populous cities, seems to

promise him an everlasting remembrance; notwithstanding he has

himself composed many and lasting works; yet I am persuaded, the

mentioning of him in your immortal writings, will greatly

contribute to render his name immortal. Happy I esteem those to

be to whom by provision of the gods has been granted the ability

either to do such actions as are worthy of being related or to relate

them in a manner worthy of being read; but peculiarly happy are

they who are blessed with both these uncommon talents: in the

number of which my uncle, as his own writings and your

history will evidently prove, may justly be ranked. It is with

extreme willingness, therefore, that I execute your commands; and

should indeed have claimed the task if you had not enjoined it. He

was at that time with the fleet under his command at Misenum.92

On the 24th of August, about one in the afternoon, my mother

desired him to observe a cloud which appeared of a very unusual

size and shape. He had just taken a turn in the sun93 and, after

bathing himself in cold water, and making a light luncheon, gone

back to his books: he immediately arose and went out upon a rising

ground from whence he might get a better sight of this very

uncommon appearance. A cloud, from which mountain was

uncertain, at this distance (but it was found afterwards to come

from Mount Vesuvius), was ascending, the appearance of which I

cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to

that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a

very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of

branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that

impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upwards,

or the cloud itself being pressed back again by its own weight,

expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes

bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either

more or less impregnated with earth and cinders. This

phenomenon seemed to a man of such learning and research as my

uncle extraordinary and worth further looking into. He ordered a

light vessel to be got ready, and gave me leave, if I liked, to

accompany him. I said I had rather go on with my work; and it so

happened, he had himself given me something to write out. As he

was coming out of the house, he received a note from Rectina, the

wife of Bassus, who was in the utmost alarm at the imminent

danger which threatened her; for her villa lying at the foot of

Mount Vesuvius, there was no way of escape but by sea; she

earnestly entreated him therefore to come to her assistance. He

accordingly changed his first intention, and what he had begun

from a philosophical, he now carries out in a noble and generous

spirit. He ordered the galleys to be put to sea, and went himself on

board with an intention of assisting not only Rectina, but the

several other towns which lay thickly strewn along that beautiful

coast. Hastening then to the place from whence others fled with

the utmost terror, he steered his course direct to the point of

danger, and with so much calmness and presence of mind as to be

able to make and dictate his observations upon the motion and all

the phenomena of that dreadful scene. He was now so close to the

mountain that the cinders, which grew thicker and hotter the

nearer he approached, fell into the ships, together with pumice-

stones, and black pieces of burning rock: they were in danger too

not only of being aground by the sudden retreat of the sea, but also

from the vast fragments which rolled down from the mountain,

and obstructed all the shore. Here he stopped to consider whether

he should turn back again; to which the pilot advising him,

"Fortune," said he, "favours the brave; steer to where Pomponianus

is." Pomponianus was then at Stabiae,94 separated by a bay, which

the sea, after several insensible windings, forms with the shore. He

had already sent his baggage on board; for though he was not at

that time in actual danger, yet being within sight of it, and indeed

extremely near, if it should in the least increase, he was

determined to put to sea as soon as the wind, which was blowing

dead in-shore, should go down. It was favourable, however, for

carrying my uncle to Pomponianus, whom he found in the greatest

consternation: he embraced him tenderly, encouraging and urging

him to keep up his spirits, and, the more effectually to soothe his

fears by seeming unconcerned himself, ordered a bath to be got

ready, and then, after having bathed, sat down to supper with great

cheerfulness, or at least (what is just as heroic) with every

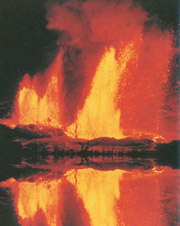

appearance of it. Meanwhile broad flames shone out in several

places from Mount Vesuvius, which the darkness of the night

contributed to render still brighter and clearer. But my uncle, in

order to soothe the apprehensions of his friend, assured him it was

only the burning of the villages, which the country people had

abandoned to the flames: after this he retired to rest, and it is most

certain he was so little disquieted as to fall into a sound sleep: for

his breathing, which, on account of his corpulence, was rather

heavy and sonorous, was heard by the attendants outside. The

court which led to his apartment being now almost filled with

stones and ashes, if he had continued there any time longer, it

would have been impossible for him to have made his way out. So

he was awoke and got up, and went to Pomponianus and the rest of

his company, who were feeling too anxious to think of going to

bed. They consulted together whether it would be most prudent to

trust to the houses, which now rocked from side to side with

frequent and violent concussions as though shaken from their very

foundations; or fly to the open fields, where the calcined stones

and cinders, though light indeed, yet fell in large showers, and

threatened destruction. In this choice of dangers they resolved for

the fields: a resolution which, while the rest of the company were

hurried into by their fears, my uncle embraced upon cool and

deliberate consideration. They went out then, having pillows tied

upon their heads with napkins; and this was their whole defence

against the storm of stones that fell round them. It was now day

everywhere else, but there a deeper darkness prevai1ed than in the

thickest night; which however was in some degree alleviated by

torches and other lights of various kinds. They thought proper to

go farther down upon the shore to see if they might safely put out

to sea, but found the waves still running extremely high, and

boisterous. There my uncle, laying himself down upon a sail cloth,

which was spread for him, called twice for some cold water, which

he drank, when immediately the flames, preceded by a strong

whiff of sulphur, dispersed the rest of the party, and obliged him to

rise. He raised himself up with the assistance of two of his

servants, and instantly fell down dead; suffocated, as I conjecture,

by some gross and noxious vapour, having always had a weak

throat, which was often inflamed. As soon as it was light again,

which was not till the third day after this melancholy accident, his

body was found entire, and without any marks of violence upon it,

in the dress in which he fell, and looking more like a man asleep

than dead. During all this time my mother and I, who were at

Misenum--but this has no connection with your history, and you

did not desire any particulars besides those of my uncle's death; so

I will end here, only adding that I have faithfully related to you

what I was either an eye-witness of myself or received

immediately after the accident happened, and before there was

time to vary the truth. You will pick out of this narrative whatever

is most important: for a letter is one thing, a history another; it is

one thing writing to a friend, another thing writing to the public.

Farewell.

LXVI - TO CORNELIUS TACITUS

The letter which, in compliance with your request, I wrote to you

concerning the death of my uncle has raised, it seems, your

curiosity to know what terrors and dangers attended me while I

continued at Misenum; for there, I think, my account broke off:

Though my shocked soul recoils, my tongue shall tell.

My uncle having left us, I spent such time as was left on my

studies (it was on their account indeed that I had stopped behind),

till it was time for my bath. After which I went to supper, atmd

then fell into a short and uneasy sleep. There had been noticed for

many days before a trembling of the earth, which did not alarm us

much, as this is quite an ordinary occurrence in Campania; but it

was so particularly violent that night that it not only shook but

actually overturned, as it would seem, everything about us. My

mother rushed into my chamber, where she found me rising, in

order to awaken her. We sat down in the open court of the house,

which occupied a small space between the buildings and the sea.

As I was at that time but eighteen years of age, I know not whether

I should call my behaviour, in this dangerous juncture, courage or

folly; but I took up Livy, and amused myself with turning over that

author, and even making extracts from him, as if I had been

perfectly at my leisure. Just then, a friend of my uncle's, who had

lately come to him from Spain, joined us, and observing me sitting

by my mother with a book in my hand, reproved her for her

calmness, and me at the same time for my careless security:

nevertheless I went on with my author. Though it was now

morning, the light was still exceedingly faint and doubtful; the

buildings all around us tottered, and though we stood upon open

ground, yet as the place was narrow and confined, there was no

remaining without imminent danger: we therefore resolved to quit

the town. A panic-stricken crowd followed us, and (as to a mind

distracted with terror every suggestion seems more prudent than its

own) pressed on us in dense array to drive us forward as we came

out. Being at a convenient distance from the houses, we stood still,

in the midst of a most dangerous and dreadful scene. The chariots,

which we had ordered to be drawn out, were so agitated backwards

and forwards, though upon the most level ground, that we could

not keep them steady, even by supporting them with large stones.

The sea seemed to roll back upon itself, and to he driven from its

banks by the convulsive motion of the earth; it is certain at least

the shore was considerably enlarged, and several sea animals were

left upon it. On the other side, a black and dreadful cloud, broken

with rapid, zigzag flashes, revealed behind it variously shaped

masses of flame: these last were like sheet-lightning, but much

larger. Upon this our Spanish friend, whom I mentioned above,

addressing himself to my mother and me with great energy and

urgency: " If your brother," he said, "if your uncle be safe, he

certainly wishes you may be so too; but if he perished, it was his

desire, no doubt, that you might both survive him: why therefore

do you delay your escape a moment?" We could never think of our

own safety, we said, while we were uncertain of his. Upon this our

friend left us, and withdrew from the danger with the utmost

precipitation. Soon afterwards, the cloud began to descend, and

cover the sea. It had already surrounded and concealed the island

of Capri and the promontory of Misenum. My mother now

besought, urged, even commanded me to make my escape at any

rate, which, as I was young, I might easily do; as for herself, she

said, her age and corpulency rendered all attempts of that sort

impossible; however, she would willingly meet death if she could

have the satisfaction of seeing that she was not the occasion of

mine. But I absolutely refused to leave her, and, taking her by the

hand, compelled her to go with me. She complied with great

reluctance, and not without many reproaches to herself for

retarding my flight. The ashes now began to fall upon us, though in

no great quantity. I looked back; a dense dark mist seemed to be

following us, spreading itself over the country like a cloud. "Let us

turn out of the high-road," I said, "while we can still see, for fear

that, should we fall in the road, we should be pressed to death in

the dark, by the crowds that are following us." We had scarcely sat

down when night came upon us, not such as we have when the sky

is cloudy, or when there is no moon, but that of a room when it is

shut up, and all the lights put out. You might hear the shrieks of

women, the screams of children, and the shouts of men; some

calling for their children, others for their parents, others for their

husbands, and seeking to recognise each other by the voices that

replied; one lamenting his own fate, another that of his family;

some wishing to die, from the very fear of dying; some lifting their

hands to the gods; but the greater part convinced that there were

now no gods at all, and that the final endless night of which we

have heard had come upon the world.95 Among these there were

some who augmented the real terrors by others imaginary or

wilfully invented. I remember some who declared that one part of

Misenum had fallen, that another was on fire; it was false, but they

found people to believe them. It now grew rather lighter, which we

imagined to be rather the forerunner of an approaching burst of

flames (as in truth it was) than the return of day: however, the fire

fell at a distance from us: then again we were immersed in thick

darkness, and a heavy shower of ashes rained upon us, which we

were obliged every now and then to stand up to shake off,

otherwise we should have been crushed and buried in the heap. I

might boast that, during all this scene of horror, not a sigh, or

expression of fear, escaped me, had not my support been

grounded in that miserable, though mighty, consolation, that all

mankind were involved in the same calamity, and that I was

perishing with the world itself. At last this dreadful darkness was

dissipated by degrees, like a cloud or smoke; the real day returned,

and even the sun shone out, though with a lurid light, like when an

eclipse is coming on. Every object that presented itself to our eyes

(which were extremely weakened) seemed changed, being covered

deep with ashes as if with snow. We returned to Misenum, where

we refreshed ourselves as well as we could, and passed an anxious

night between hope and fear; though, indeed, with a much larger

share of the latter: for the earthquake still continued, while many

frenzied persons ran up and down heightening their own and their

friends' calamities by terrible predictions. However, my mother

and I, notwithstanding the danger we had passed, and that which

still threatened us, had no thoughts of leaving the place, till we

could receive some news of my uncle.

And now, you will read this narrative without any view of inserting

it in your history, of which it is not in the least worthy; and indeed

you must put it down to your own request if it should appear not

worth even the trouble of a letter. Farewell.

PLINY THE YOUNGER